Boiled in Struggle, Brewed in Hope: The Life of Dilli Koirala

Dirgha Raj Upadhyay

If success is measured by a house, a car, and savings in the bank, then he does not fit into that definition. In a country like America, where the number of gas stations, liquor stores, and restaurants a person owns is often seen as the yardstick of success, the life he has lived, his struggles and achievements, are a source of inspiration to many.

His life resembles the story of a movie. When you hear about the scarcity, hunger, and sleepless nights he endured, it becomes clear that those who remain standing after being struck a thousand times by time and fate, eventually achieve extraordinary success. Dilli Koirala is one of them.

He was born on September 25, 1968, in the Koirala family of Shanti Chowk, Buddhashanti Rural Municipality–1, Jhapa. He was the second child among the seven children of Trilochan and Ramadevi Koirala—four sons and three daughters.

His mother passed away when he was just 13. His father ran a rice and grain business. All the family's property was spent on the prolonged treatment of his mother, who was suffering from cancer. Despite the effort, she passed away during treatment in Siliguri.

In 1985, he was studying in grade 8 at Buddha Adarsha Secondary School. A manager from Agricultural Development Bank took him to Kathmandu, promising to support his studies. But instead of sending him to school, he was made to work. When his elder brother found out, he brought Dilli back to Jhapa.

Two years later, Dilli sat for his SLC exams from Jhapa. Shortly afterward, he quietly left for Kathmandu with only a thousand rupees in his pocket—money he had earned himself. The bus fare cost him 125 rupees. He was accompanied by his friend Narendra Shrestha, whose brother worked in the Patan Industrial Area. Dilli went there but left after two days when he couldn’t find work.

He then approached Kumar Budhathoki, who was then Assistant Minister for Water Resources and also from Jhapa, asking him to help find a job. Budhathoki recommended him to the Nepali Army. However, he was not selected due to his skinny physique. He was instead offered a kitchen job. Unhappy with the Army's strict discipline, he quit after a month and a half.

During the day, he would wander looking for work. At night, he slept on a stone platform in Dillibazar with only a bag containing one pair of clothes. His money was running out. He survived on beaten rice and water, used the bag as a pillow, and spent four nights like this.

On the fifth day, he found a job washing dishes at Sekuwa Corner in Putalisadak. Two months later, he became a waiter, earning 200 rupees a month. After the restaurant closed each night, he would push two tables together and sleep on them. He saved up his earnings and bought a mattress and blanket. He was a waiter now.

One of the restaurant’s regular customers owned a garage in Kalimati. Six months later, Dilli began working at that garage, where he learned to fix vehicles and drive a taxi. Without a room to stay in, he slept inside the cars. After two and a half years, he left and started driving a taxi. Later, he got a bus driver’s license, left the taxi, and worked as a bus assistant. The driver was Ram Bahadur Thakkar from Hetauda. Thanks to Thakkar’s recommendation, Dilli began driving a bus on the Kathmandu route in 1993.

His bus ran from Jhapa to Kathmandu on Wednesdays, and later from Birgunj and Katari. After a year, he left that job too and started driving a local bus from Kathmandu to Dhulikhel. Students from Dhulikhel school were his regular passengers. One girl, who boarded the bus from Banepa daily, refused to travel in any other vehicle. She waited only for his bus.

In time, he fell in love with that girl. She was studying in Grade 8. When he found out she was about to be married off, he eloped with her to Jhapa. His family disapproved of the marriage because she was a Chhetri. They returned to Kathmandu, and Dilli resumed driving a bus between Kathmandu and Birgunj. He rented a room in Hetauda and settled there with his wife.

A year later, he came into contact with Dr. Homanath Dahal, owner of Asian Pharmaceuticals. Dahal ran a medical shop in front of Bir Hospital. Dilli began driving Dahal’s car. Soon after, Dahal helped him buy a taxi with a loan from a finance company. Dilli drove the taxi and also delivered medicine for the shop.

Six months later, he was diagnosed with jaundice. He handed over the taxi to another driver and returned to his village. When he came back, the driver had vanished, the taxi was damaged, and parked at the garage. Before the finance company could repossess it, Dahal took responsibility, and Dilli moved on.

In 1996, he met Furpa Gyalzen Sherpa, owner of Himalayan Sherpa Adventure. Dilli started working for his trekking company, transporting tourists. Through his contact with foreigners, he learned English.

In 2003, he joined the French company Randonées Himalayas, which later took him to France in 2008. After returning, he continued in the trekking business.

In 2012, he arrived in the U.S. on a tourist visa during Christmas and stayed with AC Sherpa, who ran a trekking company. Four months later, he returned to Nepal with two tourist groups sent by AC’s company. A month and a half after they returned, Dilli went back to the U.S.

During his time at Himalayan Sherpa Adventure, he had met Pemba Sherpa, who ran a trekking company in Boulder, Colorado. Pemba used to bring foreign tourists to Nepal. He invited Dilli to Boulder, and Dilli came from Seattle.

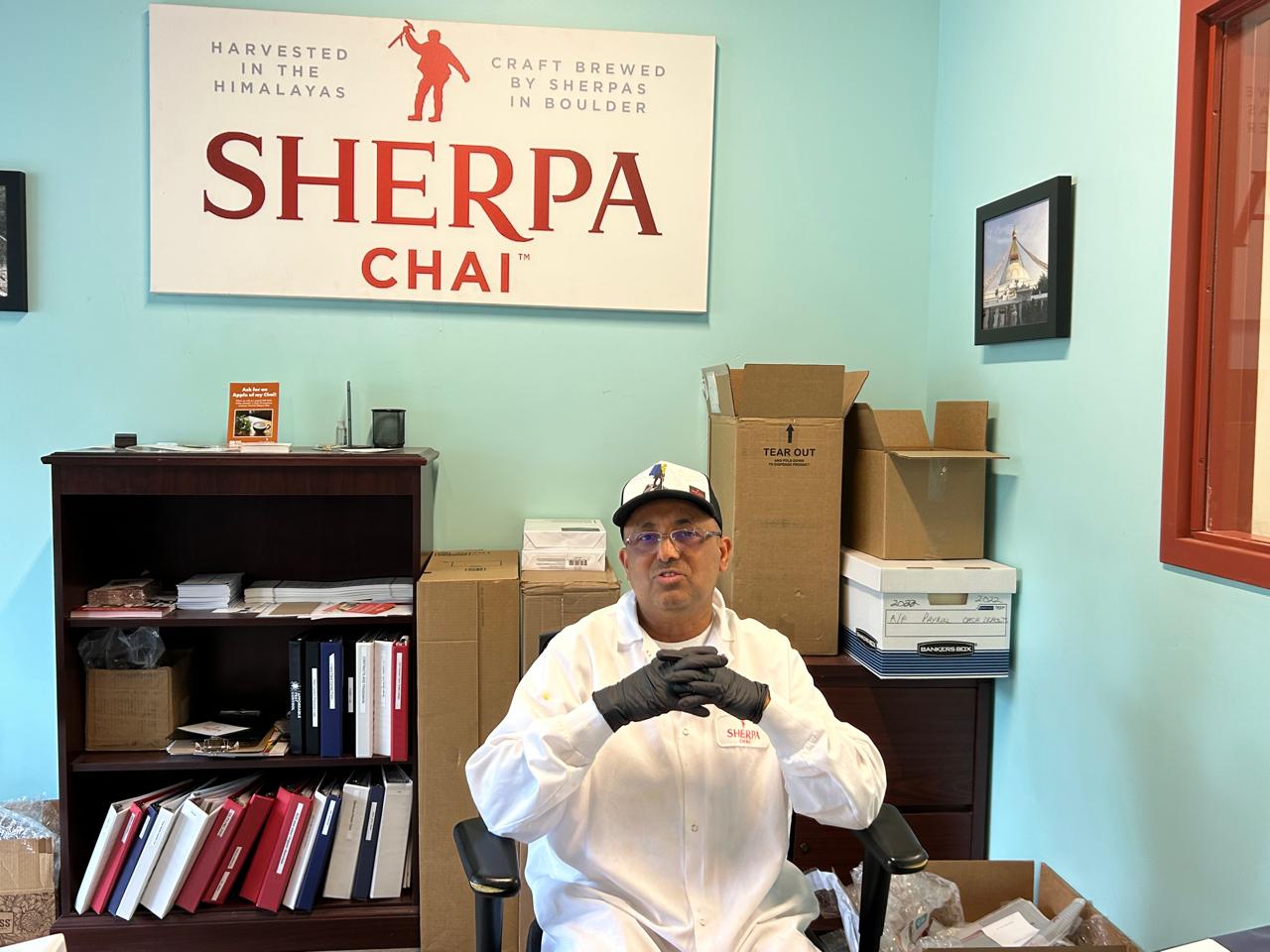

Pemba also ran a restaurant in Boulder. Dilli began working there. Pemba had a dream of launching a tea business. Dilli supported the idea and began brewing Nepali-style tea at the restaurant. Working day and night to fulfill Pemba’s dream of introducing ready-to-drink Nepali tea to Americans, their experiment succeeded. Within a year, they introduced a ready-to-drink tea brand named Sherpa Chai.

.jpeg)

In 2013, Pemba registered Sherpa Chai. To support the tea industry, Dilli completed a three-month microbiology course. Since the restaurant couldn’t handle large-scale production, they opened a separate facility. Pemba offered him a small percentage of ownership.

In 2015, Sherpa Chai partnered with Whole Foods, followed by Kroger in 2016. Initially made in the restaurant until the end of 2016, the increasing demand led them to expand production. The factory they opened in 2017 soon became too small. Since then, as the business expanded, they’ve relocated four times. Starting in a few local stores and coffee shops in Boulder, Sherpa Chai is now sold across all 50 states of the U.S. through Kroger and Whole Foods.

Dilli is now the Head of Production and a shareholder at Sherpa Chai. The tea he produces comes in seven flavors, including ginger, fennel, and cardamom. The blend requires no additional spices or sugar and avoids the hassle of straining. It’s tea in a pouch—ready to enjoy hot or cold.

Sherpa Chai is the first Nepali-origin business to sell its product in all 50 states of the U.S., promoting Nepali tea in the American market.

While the ginger comes from Peru and sugar from Colombia, Dilli still uses Nepali tea leaves and cardamom.

(2).jpeg) He’s equally involved in social work. Remembering the pain of his mother’s cancer treatment due to lack of blood, he became a regular blood donor—over 20 times. He once saved a mother and her infant by donating blood at a critical moment.

He’s equally involved in social work. Remembering the pain of his mother’s cancer treatment due to lack of blood, he became a regular blood donor—over 20 times. He once saved a mother and her infant by donating blood at a critical moment.

Once, while leading a trek to Bhojpur, he saw a group of people carrying a woman on a stretcher. Two days later, he found out she had died before reaching the maternity center. He posted about it online and appealed to foreigners for help. Soon, foreign donors contributed 40,000 euros, and a health post was built.

He established an endowment fund of Rs. 550,000 in the name of his mother at his old school, Buddha Adarsha Secondary School, which has been providing scholarships to four students annually since 2019.

In 2014, he donated $1,000 for the reconstruction of Tengboche Monastery in Solukhumbu. He contributed Rs. 300,000 for a senior citizen rest pavilion in Hokshe, Budhabare-3. During the floods and landslides in Kavre, he sent $500. He didn’t stay silent during COVID or the earthquake either—he sent aid. He lives in the U.S., but his heart remains in Nepal. He returned in 2016, 2022, and 2024.

Even amidst the prosperity of America, he has not forgotten that old stone platform in Dillibazar—where he lay hungry for many nights, resting his head on a bag, dreaming of a better life. He remembers the starlit nights he spent counting stars, wondering when the dawn would arrive.

He still remembers Dhobi Khola’s sparkling water, which he drank without a care for disease. He bathed there freely, planted peanuts by the banks, and saw the river’s clear sands—something he cannot find in Colorado’s Boulder, Louisville, Golden, Gunnison, or Crested Butte. In all these places, he searches for Budhabare, Jhapa.

His wife, Lila Koirala, stood by him through every hardship. To support him, she even learned to drive a tempo and worked Kathmandu’s streets for over six months. When the children needed her, she stayed home without complaint, never once saying she was in pain. She raised their two children as he worked in America.

Their daughter Amrita earned a Master’s in IT. Their son Amrit is a national basketball player and currently pursuing a Master’s in Sports Science.

Many blame their geography or circumstances for their failures. Dilli never did. He accepted everything—scarcity, pain, loss, and hunger. He endured the loss of his mother, countless hardships, and sleepless nights. But he never gave up.

In a society where men are not supposed to cry, he bore his pain in silence. He smiled through it all.

At that time, Kathmandu was the city of dreams. Who dared to dream of America? When he left Jhapa for Kathmandu, he had no dreams. Marriage brought responsibility. The environment of Kathmandu nurtured dreams within him. Those dreams led him to America. Within him was a fierce determination to fulfill them. He didn’t know how to give up.

He may never have attended university, but his life experience—his struggle, his hunger—teaches a lesson no academic curriculum can. His life declares: those who remain standing in their darkest hour, carve history.

.jpeg)

2025-06-25-05-59-42.jpeg)

तपाईको प्रतिक्रिया